As a petrographer, I have had the opportunity to examine many historic mortars and historic concretes from around the United States. They silently tell stories about natural elements and sometimes, human ingenuity.

One historic mortar I studied holds special meaning on a personal level. It was a stone-veneer mortar from the foundation of a long-abandoned copper stamp mill in southern Michigan. As a kid, I often explored the old ruins with my cousins who lived near the abandoned structure. More recently, I attended a family reunion and discovered that my grandfather worked at the stamp mill. He died in 1937 as the result of an accident there.

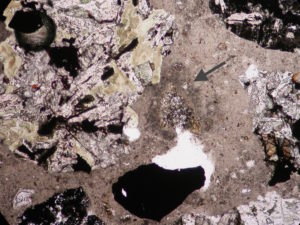

The stamp mill was a wood structure built circa 1890 and had a foundation with a veneer comprised of red sandstone and stone-veneer mortar similar to that in Photograph 1.

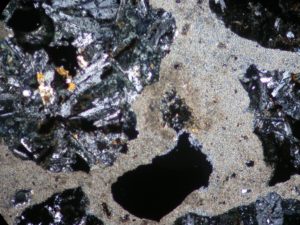

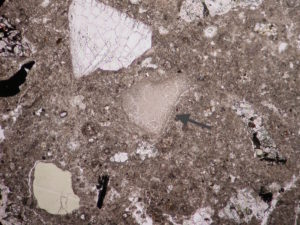

During my last visit, ever the petrographer, I obtained a sample of the stone veneer in order to assess what the mortar and stone were made of. Thin section examination indicated that the mortar contained large residual portland cement clinker particles together with hydrated lime and a sharp sand (Photographs 2 and 3).

The large size of the residual portland cement clinker particles is consistent with the manufacturing practices in the late 1800’s. The presence of lime is based on the general microstructure of the paste along with the presence of residual hydrated lime lumps (Photograph 4).

The sand was comprised essentially of volcanic rock fragments that were primarily angular in shape. The fragments contained a relative abundance of opaque minerals that, when viewed under reflected light, are consistent with copper (Photograph 5).

The use of portland cement in 1890 is interesting since the annual US production of natural cement was more than 20 times greater than portland cement. It wasn’t until 1900 that portland cement surpassed natural cement in annual production.

My other interesting finding was that based on the presence of what some might call mineable quantities of copper, the stampings were used as the aggregate in the mortar!

Plane-polarized light. Field Length = 1.67 mm